Mal-alignment: the scourge of modern day health care practitioners. According to many, it is the root of all clinical evil in the orthopedic world. It has been used to rationalize countless clinical scenarios and treatment interventions.

Mal-alignment: the scourge of modern day health care practitioners. According to many, it is the root of all clinical evil in the orthopedic world. It has been used to rationalize countless clinical scenarios and treatment interventions.

Rumor has it that resolution of this malady is also the solution to world hunger and peace in the Middle East. But I digress.

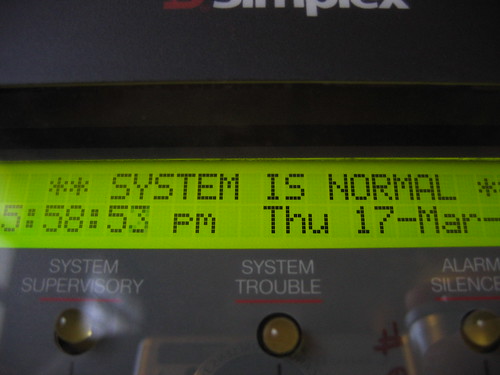

Oh, mal-alignment. How you tantalize us with the hypothetical world in which you contribute so much to so many. But understanding you would require a deeper understanding of "normal" first, now wouldn't it?

Which brings us to - the inconvenient truth about normal.

So just what is "normal"? On one side of that normal distribution, you have patients that are asymptomatic and have horrible alignment and/or symmetry; on the other side, you have patients that are symptomatic and have great alignment and/or symmetry. And then you have the vast majority in the middle, those considered "normal".

Reid (1992) noted that “mal-alignment is a term that should be reserved for gross abnormalities, two standard deviations outside the norm”. Statistically speaking, that doesn't leave a large percentage of the population that are "abnormal".

This line of reasoning regarding normal extends into imaging studies. Take, for example, the lumbar spine. There will be 70% of asymptomatic lumbar spines that have an abnormal MRI. Depending on the study, 50 - 90% of asymptomatic shoulders have a partial thickness tear of the rotator cuff on MRI. Knee MRI? Chances are good you are painfree and fully functional yet have a meniscal tear on MRI. Similar issues exist with radiography. People can have osteoarthritic joints that are painfree, and pristine joints that have pain. And all points in between.

Welcome to the majority. Welcome to normal.

Perhaps most importantly, having a positive MRI or significant mal-alignment doesn't necessarily tell me much about your presenting problem, your lack of function, or your future. It needs context.

Can there be some scientific plausibility to a relationship between mal-alignment and the onset of symptoms? Yes. A great example is the acute lateral shift that can occur with an episode of low back pain. The patient reports being "straight", then is suddenly shifted with the onset of their symptoms and loss of function. There is a mechanical cause-and-effect relationship in time and space. There is relevance and context. The patient can relate the onset of symptoms to changes in their "normal" alignment and function - whatever that is.

But in most clinical situations, clinicians make a quantum leap in thinking by relating mal-alignment and asymmetry to the onset of symptoms and loss of function. This is a problem of thinking more so than a lack of relationship between variables.

Clinicians embrace mal-alignments and asymmetries because they promote endless hypotheses that can rationalize just about any treatment intervention. Mal-alignments and asymmetries have the potential to create countless treatment sessions while trying to make the patient “normal”. Those "treatment" interventions could, in fact, be addressing something that is already normal for that patient. Unfortunately, this line of clinical reasoning leaves us with a bit of a conundrum. No, let me rephrase that - a logical fallacy.

So what do we do now? Do we maintain the contradiction in our thinking? Or do we change our paradigm?

Health care providers as a whole can choose - right now - to let go of the belief. They can eradicate these logical fallacies. But in doing so, there will be a significant degree of discomfort in doing so. You can either fight the emotions, maintain the contradiction, and defend your stance - or you can acknowledge the reasoning, integrate it into a better scientific methodology, and move forward.

Which one do you choose? And which one is best for the patient?

Photo credits: skpy

"Running Injuries: Etiology And Recovery- Based Treatment" (co-author Bridget Clark, PT) appears in the third edition and fourth editions of "Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation: A Team Approach" by Charles Giangarra, MD and Robert C. Manske, PT.

"Running Injuries: Etiology And Recovery- Based Treatment" (co-author Bridget Clark, PT) appears in the third edition and fourth editions of "Clinical Orthopaedic Rehabilitation: A Team Approach" by Charles Giangarra, MD and Robert C. Manske, PT.

Allan Besselink, PT, DPT, Ph.D., Dip.MDT has a unique voice in the world of sports, education, and health care. Read more about Allan here.

Allan Besselink, PT, DPT, Ph.D., Dip.MDT has a unique voice in the world of sports, education, and health care. Read more about Allan here.

Top 5 finalist in three categories: "Best Overall Blog", "Best PT Blog" and "Best Advocacy Blog".

Top 5 finalist in three categories: "Best Overall Blog", "Best PT Blog" and "Best Advocacy Blog".